Britain has a lot of golf courses: over a quarter of Europe’s courses are located within the United Kingdom. That’s two-and-a-half times that of the next most numerous country: 1,800 compared to Germany’s 731 – or one course for every 37,000 people, with each German course serving 113,500.

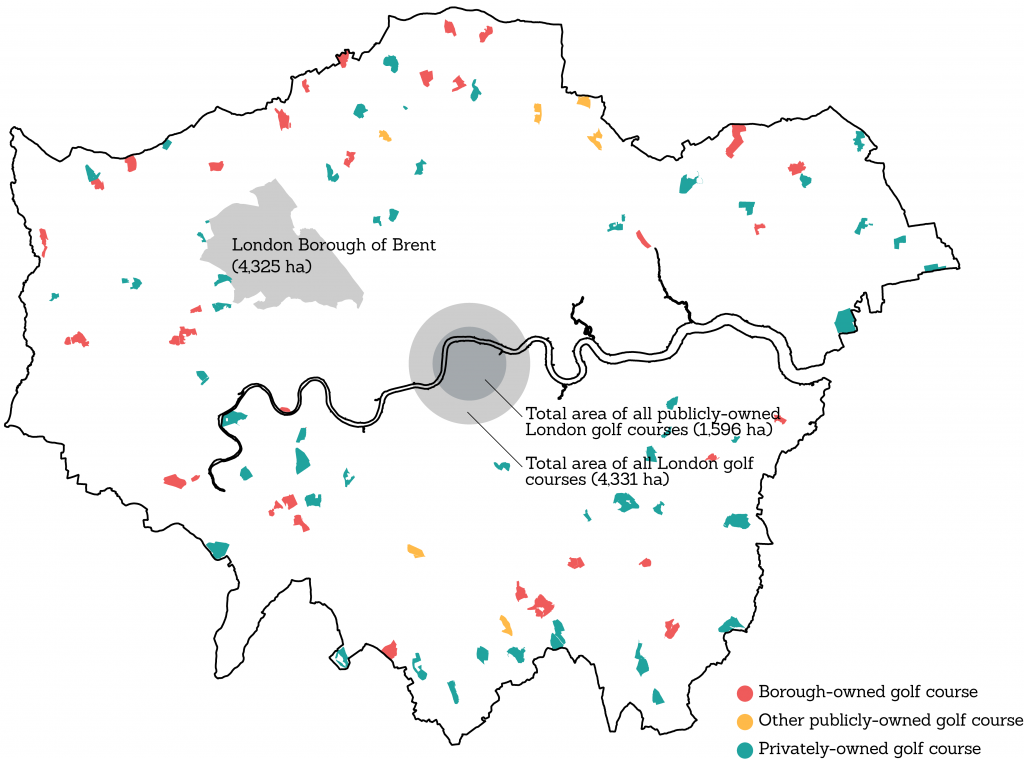

Imagine a typical golf course and your mind might conjure up images of rolling, emerald fairways of the home counties or rugged, windswept heathlands of the Scottish coast. Yet it might be surprising to learn that, despite London taking up around 0.65% of the UK’s total area, over 1 in 20 of the country’s golf courses lie within it. There are no fewer than 94 active golf courses (excluding driving ranges and courses with fewer than 9 holes) located within the Greater London area, together covering an area of 4,331 hectares. 21 of London’s boroughs have at least one course; some, such as Enfield, have seven.

For regular players, golf represents an opportunity to spend time outside with friends and colleagues, taking in the fresh air and exercise. Yet given the capital’s myriad constraints on development, it’s surely a stretch to claim that a leisure activity enjoyed by around 1% of the national population (a figure which is likely far less when only the population of London is taken into account) requires such huge tracts of land within a city which is in such dire need of homes?

Below I have set out how I believe that limited, sensitive, development of a small proportion of London’s golf courses could make a significant impact on meeting the city’s housing need as well enhancing biodiversity and opening up vital green space for the benefit of all Londoners.

The London Borough of Golf

The area of Greater London given over to golf courses is vast. If golf courses were a London Borough in their own right, it would be the 15th largest; bigger than Brent (total population: 330,800), and slightly smaller than Sutton. Even discounting privately-owned courses from the measurement, the 43 publicly-owned golf courses in London take up just under 1,600 hectares of land in Greater London. That’s still more than the entire area of Hammersmith & Fulham, which has a population of 185,000.

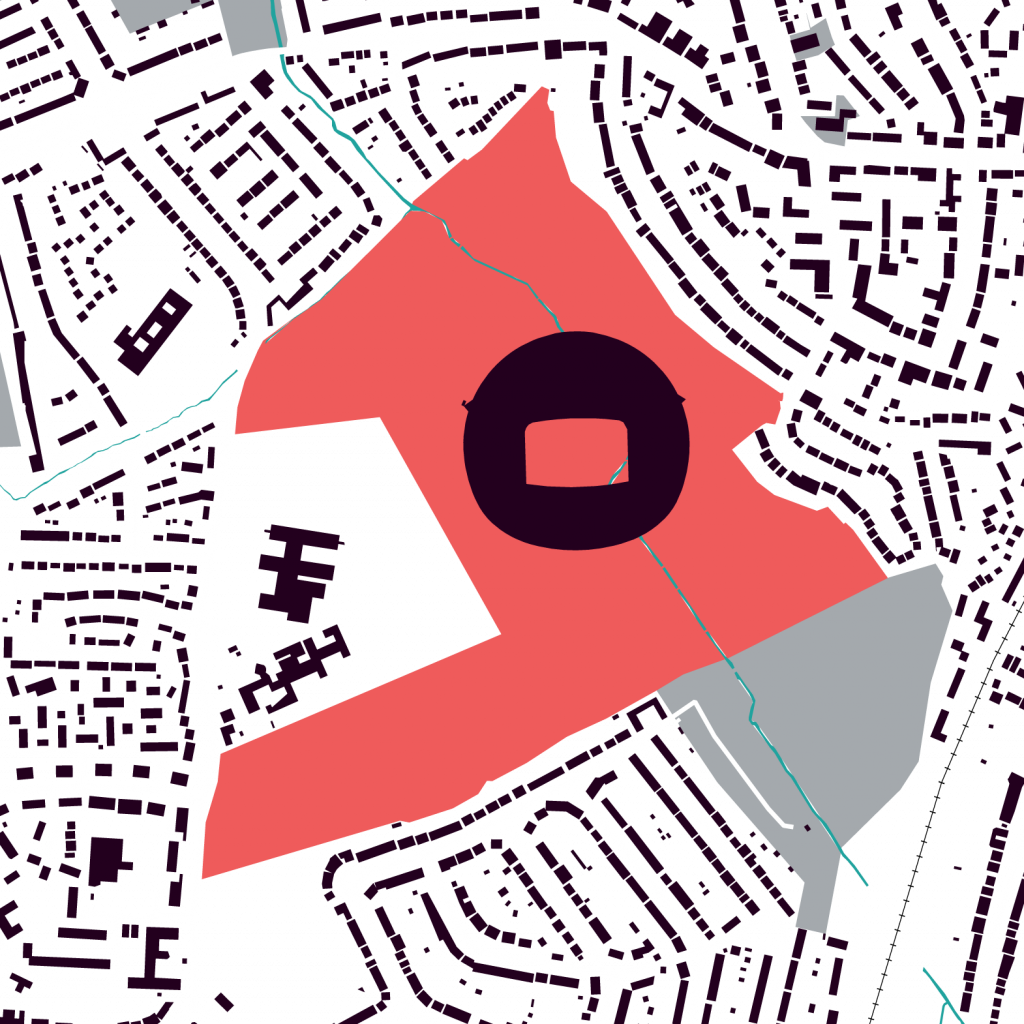

On average across London, a single hole occupies an area of just over 2.5 hectares (to arrive at this figure I’ve divided the total area of London’s golf couses by the number of holes the provide). That means the average 18 hole course in London has a total area of approximately 46 hectares. It’s difficult to overstate how large this is. To give a sense of scale, the following image shows the outline of Wembley Stadium overlaid on a map of Enfield Golf Course. It fits comfortably within it, taking up the area of just two holes. Wembley Stadium seats 90,000 people. The Excel centre – one of London’s largest buildings – fits comfortably inside it too.

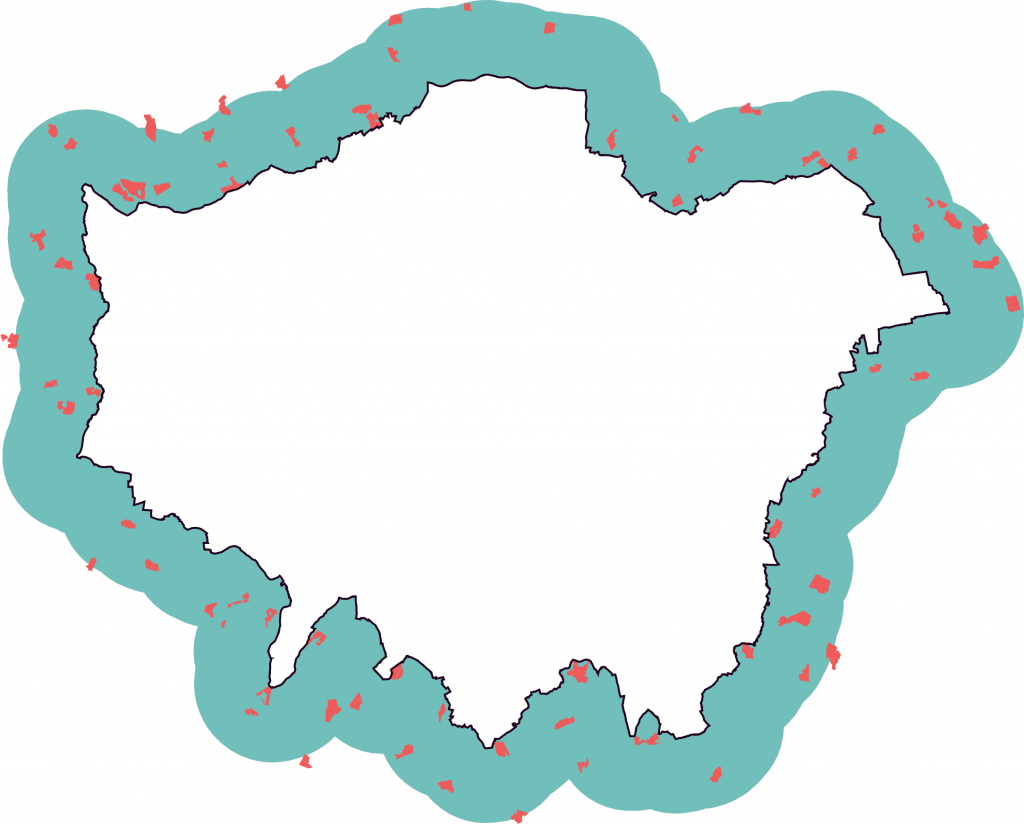

Those living on the fringes of London aren’t limited to playing only on courses within its boundaries, however. There are a further 74 golf courses with an area exceeding 10 hectares within just 5km of London’s boundary, as the following diagram shows:

Who owns London’s Golf Courses?

43 of London’s golf courses are within public ownership, mostly by the London Boroughs themselves. Others are owned by public bodies including the Church of England through the Church Commissioners (perhaps the recent “Coming Home” report by the Archbishops’ Commission on Housing, Church and Community might stimulate some discussions as to whether its 30 hectares of land in Barnet might be put to better use?).

In most cases the freehold is owned by the council and leased to the golf clubs which occupy them; a handful are operated as municipal courses.

Then there are the anomolies: Arkley Golf Club (freehold owned by London Borough of Barnet) has recently been acquired by developer U+I having bought the lease from the club for £300,000 (roughly £14,000 per hectare). Whilst claiming that this would “secure” the future of the club, Matthew Weiner of U+I was careful to point out that such acquisitions “have the potential for longer-term value creation”. Arkley Gold Club lies entirely within the green belt, however with the new London Plan loosening restrictions on the protection of green belt, perhaps this is a canny move given the average property prices in this part of Barnet currently exceed £1m. In it’s draft Local Plan, Enfield Council is already proposing the selective release of some of its green belt to meet housing need which has, inevitably, raised the hackles of locals.

But perhaps these courses are a good source of income for cash-strapped councils? Seemingly not. Enfield Golf Club, to take one example, pays an annual sum of £13,500 to the council for the privilege of renting its 39 hectare golf course in the west of the Borough. That’s slightly less than it costs to rent a two-bedroom flat in the same area for a year.

The remaining courses are owned by various public and private bodies: pension funds, the clubs themselves. The City of London Corporation holds the freehold to two (one in Redbridge and another in Waltham Forest, totalling over 90 hectares of land) and the Crown a further five (three of which are in Richmond-upon-Thames).

Types of Green Space

According to the Ordnance Survey’s Open Green Space dataset, there is 23,684 hectares of accessible green space within London’s boundary. This falls into a range of categories, including Allotments and Community Growing Space, Cemeteries and Public Parks & Gardens. Only three distinct leisure activities warrant their own category: bowling greens (36ha), tennis courts (65ha) and golf courses (4,331ha). Football pitches are commonly used for other uses too, so these are consolidated into a “playing field” category, taking up 2,948ha.

The total area of green space dedicated to sports and leisure in London is roughly equivalent to that of public parks and gardens (although, of course, some parks are often used for sports and games too, as a summer evening visit to Regent’s Park will testify).

Of the 9,950ha or so of land set aside for sport and leisure activities alone, 43.5% of this is dedicated to golf. Golf takes up 17% of all of the available green space in London.

Golf Courses and Planning

London’s green belt covers over 35,000 hectares, more than 22% of the city’s total area. Green belt is protected by national planning legislation as set out in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and reinforced by the Mayor of London’s regional London Plan, the most recent iteration of which was adopted in March this year.

A second form of protection, unique to London and with many of the same restrictions on development, is what’s known as Metropolitan Open Land (MOL). In addition to the green belt, MOL takes up a further 15½ thousand hectares. That means that, in total, nearly 51,000 hectares – around a third – of London’s land area is subject to strict prohibitions on development.

The majority of golf courses are protected by one of two planning designations through falling within either green belt, Metropolitan Open Land (MOL), or both. Those on the edge of the outer-London boroughs sit entirely within the green belt, generally surrounded by open countryside. Those courses closer to the centre tend to be within built-up areas or adjacent to other areas of open space. Southwark’s Dulwich & Sydenham Hill Golf Course is the closest to central London, lying just within Zone 3 of Transport for London’s fare network.

Policy G3 of the London Plan states the following about Metropolitan Open Land:

MOL protects and enhances the open environment and improves Londoners’ quality of life by providing localities which offer sporting and leisure use, heritage value, biodiversity, food growing, and health benefits through encouraging walking, running and other physical activity.

2021 London Plan

Yet the prevailing assumption that golf courses somehow convey these benefits on Londoners seems erroneous. As most people who live close to a golf course will attest, the opportunity to include these spaces as part of a daily run – let alone for planting vegetables – is not one that most Londoners enjoy.

The London Plan demands that MOL designation meet one of the following critera:

- it contributes to the physical structure of London by being clearly distinguishable from the built up area

- it includes open air facilities, especially for leisure, recreation, sport, the arts and cultural activities, which serve either the whole or significant parts of London

- it contains features or landscapes (historic, recreational, biodiversity) of either national or metropolitan value

- it forms part of a Green Chain or a link in the network of green infrastructure and meets one of the above criteria.

By their very nature, golf courses are large and generally flat. Several of London’s courses sit within urban areas, with a clear distinction between the fairways and surrounding houses. Yet many are located adjacent to other areas of open space (Perivale Golf Club in Ealing, for example, is part of a wider area of green space which includes sports pitches and two other golf courses hugging the banks of the River Brent). Arguably a distinction between open and “built up” space is of little value if nobody is around to appreciate it.

Criteria two requires MOL to provide leisure or sport facilities which serve “either the whole or significant parts of London”. One might wonder how a golf course fulfils this objective when the maximum number of people who can access it (never mind the cost of playing: many club membership fees exceed £1,000 per annum) is so limited.

The third criteria for MOL designation is that the space must include features or landscapes of national or metropolitan value. Few golf courses fulfil this requirement: some fall within Conservation Areas and others feature listed structures (the club houses at Old Ford and Hadley Wood Golf Clubs, for instance), but there are very few courses which are listed in their entirety. Stockley Park Golf Club in Hillingdon is one of the few examples of courses which benefit from this protection, and in this case simply because of its proximity to the business park which was Grade II listed only in August 2020, and not because of any heritage characteristics of the course itself.

The final criteria is that MOL must form part of a “green chain” or a link in the network of green infrastructure as well as meeting one of the above criteria. The inaccessibility of golf courses to most Londoners put paid to any notion that golf courses “promote healthier living, providing spaces for physical activity and relaxation”, however, it could be argued that they offer some environmental benefits.

By and large, it’s dubious whether most golf courses can really be said to fulfil the four criteria of MOL set out in the London Plan, and perhaps this is an opportunity to examine whether the time has come to remove the protection this offers.

The Social Value of Golf Courses

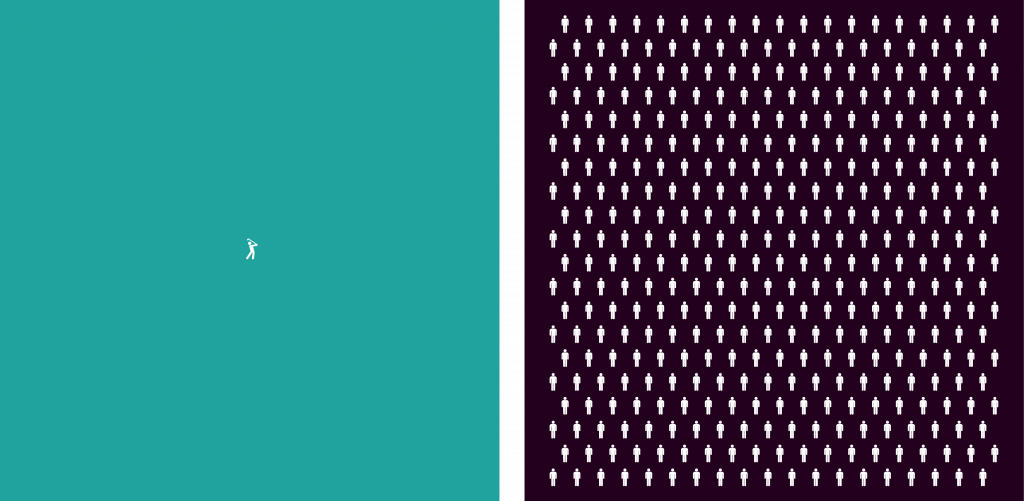

Most club rules state that no more than four players can occupy a hole at any one time. That equates to a maximum peak capacity of 6,900 individual golfers across London at any one time, although the likely number of simultaneous players is likely to be considerably less than this (all 18 holes will not be in use at the beginning of the playing day, and with limited daylight during winter months the playing window narrows considerably).

Therefore, assuming a course is at maximum capacity, this results in a total theoretical player density of 0.63 people per hectare.

In most cases, the maximum number of players playing each hole is four. So, for an 18-hole course the maximum density of people playing at any one time can be no more than 72. An 18-hole round of golf typically takes four hours to complete. During a typical summer day (8am to 8pm) that equates to a maximum number of 216 players per course.

On this basis, if Regent’s Park in central London were to become a golf course, at 166 hectares it could only be used by 105 people at the same time – or 314 people per day.

Visitor number for London’s parks are quite difficult to obtain, but August 2007 Regent’s Park actually had 809,039 visitors; or just over 26,000 visitors each day. Note that these figures are comparing the maximum daily occupancy of the average golf course with the average daily number of park visitors; the likely ratio between the two is significantly greater on popular days such as weekends and bank holidays.

It is, perhaps, unfair to compare a central London park – which is in close proximity to many residents – to a golf course, which tend to be located within the outer London boroughs.

Greenwich Park has an area of approximately 74 hectares. In August 2007 it had 560,515 visitors, equating to around 18,000 each day. That’s over 83 times the maximum capacity of Dulwich & Sydenham Hill Golf Course, which is a similar distance from the centre of London. Reducing the area of the golf course to achieve the same density of use as Greenwich Park would mean its 33 hectare area shrinking to 400 square metres – approximately one-and-a-half tennis courts.

All in all, with 1,684 holes, the total daily capacity of London’s golf courses is no more than 20,208 people: only two thousand more than the daily capacity of Greenwich Park alone. The actual figure will be far lower: this assumes a perfect summer’s day, with the holes full to capacity for the full duration of daylight hours, on every day of the week.

The demographics of golf course use suggest, perhaps unsurprisingly, that they are enjoyed predominantly by older men. Typically, three quarters of club membership tends to be men, and 80% are over 40. That’s compared to a median age of 35.6 in London.

Based on these figures, it’s hard to see a significant benefit to the physical and mental wellbeing of London’s citizens when so few can use these spaces at any one time. Perhaps in recognition of the limited social utility of its only golf course, Lewisham Council took the decision to convert Beckenham Place Park into a public park in 2017.

A Better Use of Land?

Many of London’s golf courses are located well away from areas of high population density, and perhaps don’t lend themselves to alternative uses.

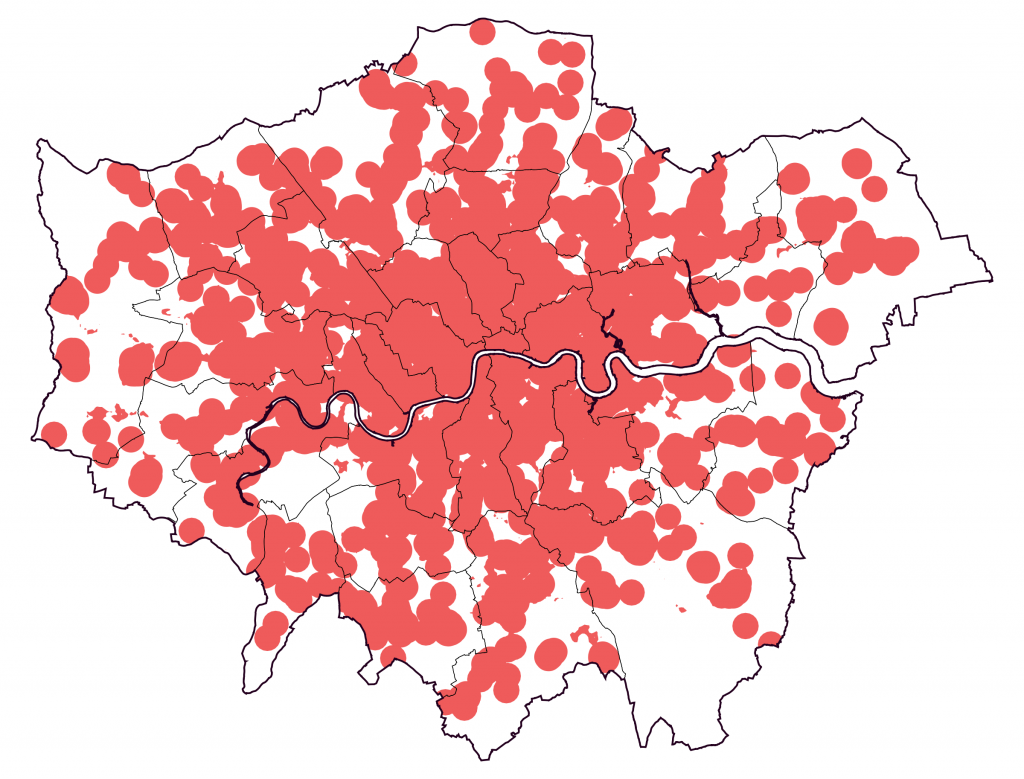

However, a surprising number are located in highly accessible areas: close to public transport or high streets. Helpfully, the new London Plan provides a useful method of assessing geographic areas for their accessibility to important infrastructure: the H2 Small Sites policy of the plan defines such areas as being appropriate for “incremental intensification”. While this policy is specifically targeted at small sites (ie. those with a total area below 0.25 hectares), it provides a useful tool for establishing suitability for new housing.

60% of London falls within this zone, although large parts of outer London, being generally further from public transport, does not (only a third of Havering meets this definition, for example). Yet fully 1,420 hectares of all London’s golf courses—and 565 hectares of publicly-owned ones—have been determined as suitable for “incremental intensification” by the Mayor of London. (It should be noted that the Mayor has strong feelings about the loss of green space in London, and that his draft London Plan placed even stronger restrictions on development on green belt and MOL which were loosened slightly at the direction of the Secretary of State during the adoption process).

So if we were, in one fell swoop, to build across all of the publicly-owned golf courses that fall within the Policy H2 zone, how many homes might we provide?

The existing density of outer London is pretty low, with most of the suburban boroughs hovering around the 25-30 dwellings per hectare mark. That’s around half that of the inner-London boroughs, although a handful exceed 70 homes per hectare. However, it seems pretty clear that we should be targeting higher levels of density for new development in most areas – and certainly those in accessible locations – if we are to have any chance of meeting London’s housing needs.

Therefore, using a (still relatively modest) target density of 60 homes per hectare, if we were able to convert all those areas of public golf courses falling within the H2 zone, London might deliver 33,900 new homes. Based on an approximate average occupation level of 3 people per household, that equates to 101,700 people.

To put this in different terms, the same area occupied by a single golfer could provide a home for around 380 people.

As of March 2019, there were 178,023 people living in temporary accommodation. By reducing London’s public golf courses by just 220 holes (13% of the total), we could reduce the number of people living in temporary accommodation by 57%. This would still leave 1,473 holes available across the city for those Londoners who still feel the need to spoil a good walk.

A Good Walk Spoiled

It seems clear that golf courses ability to meet the four criteria of MOL designation is tenuous at best. The strongest defence for their inclusion is physical distinctiveness from, and their biodiversity contribution to, an urbanising city.

Yet as our case study has demonstrated, careful and selective development – providing housing a social infrastructure in sustainable locations – can not only maintain a clear visual separation between built-up areas and open land, but also improve the quality of the green space that remains; not only in is diversity of species, tree cover and opportunities for urban agriculture and food production, but also in its accessibility to ordinary Londoners.

Perhaps now is the time for a rational discussion about whether golf courses still represent an optimal use of land and whether the councils which own them should consider putting them to a more appropriate use?

Updates

4 September 2021 – Added text and map showing the 74 gol courses which sit within 5km of Greater London’s boundary.

30 August 2021 – Section added showing types of green space in London, using Ordnance Survey Green Space dataset.

29 August 2021 – Link to Guy Shrubsole‘s research included in the section about ownership.

Congratulations on a great piece of work.

Thanks, Paul, much appreciated. Any comments for additions or improvements most welcome.

Give it a spellcheck: “approrpriate”, “the number of holes their provide”, “Typically, three quarters of members tend to be men”.

Your link in the statement, “Most club rules state that no more than four players can occupy a hole at any one time” doesn’t actually back up the statement. That rule isn’t one I’m familiar with either, let alone one enforced at “most” clubs. Anyone who’s played at a busy time would realise you don’t just have one group on anything other than a par 3 (and even then you’d have one on the green and one on the tee).

“By and large, it’s dubious whether most golf courses can really be said to fulfil the four criteria of MOL set out in the London Plan”

Your bias shows most strongly in your dismissal of any of the criteria for MOL. Your argument against the first criteria is that, “a distinction between open and “built up” space is of little value if nobody is around to appreciate it.”

Are you honestly arguing that nobody is around to appreciate it? What rule states that anyone has to be around to appreciate it?

“The inaccessibility of golf courses to most Londoners put paid to any notion that golf courses “promote healthier living, providing spaces for physical activity and relaxation”

Please explain why golf courses are inaccessible to most Londoners. Your website is at some pains to show there are lots of golf clubs, many of which are within easy access of public transport. Your point about the maximum membership fee is glib as there are always cheaper options (mid-week, junior, senior, pay as you play). Even if we do accept your assertion, why does that mean golf courses don’t provide a space for physical activity?

Out of curiosity, why limit this proposal to golf courses? I’m sure football pitches take up a lot of room. Why not them as well?

Thanks for the corrections, which I’ve now changed. The maximum capacity is based on a calcuation of a theoretical figure of 4 x 18 = 72. As far as I understand it, it’s usual practice that no more than four players can play a hole at any one time. My comment about accessibility is that once this capacity is reached, it is unlikely to be exceeded. Also, I cannot simply walk across a golf course in the same way that I can a public park. There might be limited public footpaths across it, but I would likely be unable to stop for a picnic on one of the fairways, or cycle across a putting green. I’m not making an argument that membership itself is exclusionary, but that the sheer amount of space required for this pastime is enourmous compared to other leisure uses. The OS greenspace dataset doesn’t even both distingushing between different sports uses, other than bowling greens, because they are proportionately so small.

I’m going to update the article to include a summary of relatively land use for leisure, as I think that’s an important statistic for context.

My golf course has 5 par 3 holes and 13 par 4/5 holes. On a par 4/5 hole, there will be: 4 golfers in the teeing area waiting to drive; 4 golfers on the fairway; and 4 on the green. Thus, the maximum capacity of the 13 par 4/5 holes is 12 X 13 = 156. The par 3 holes tend to be bottlenecks. Typically, there will be 4 players in the teeing area; and 8 players waiting to enter it. 4 players will be on the fairway or the green. Thus, the maximum capacity of the par 3 holes will be 16 X 5 = 80. The maximum capacity of the golf course as a whole is thus 156 + 80 = 236. Are you willing to revise your theoretical figure of 72?

Hi Ernest, thanks for the thoughtful comments, this is really useful. Yes, I’ll make a revision to the data on this basis. Do you have a rough idea about the size of your course? Not the length – one of the things I’ve struggled with is correlating the area with the length. There are many variables (length of day, average size, etc.) which affect the effective density, so I’ll run through the figures again in light of your comments.

They are inaccessible because you need to pay for each hour of access and to learn to play you need to spend x hours and you need to book and you need to take half a day off each time to finish a round. So, you also need to be able to afford all that.

Tell me, how many single mothers are members at your local golf club?

I disagree entirely. Perhaps you don’t care about or play golf but 5.6Million yearly UK players do (yes that 1% stat you mentioned isn’t true). It’s also misleading to claim that there are a disproportionate amount of golf courses based on London’s land size. If you base on population, there’s 5% of the country’s courses for 10% the population. Furthermore, suggesting that golf courses do not meet any of the criteria for MOL designation is laughable and that’s all I’ll say about that point. Finally, there are better alternative solutions to the problem (e.g. improving transport links so that loving outside of London and commuting in is viable)

Hi Sam, thanks for the comments. I’m interested to know which part of the MOL definition you think golf courses meet? I’ve stated that I can just about buy the idea that they represent a distinction between built-up areas and open space, but they are not “accessible” to the general public in any meaningful way. They also don’t, in most cases, act as part of a “green chain”. So I really can’t see how they meet the definition of MOL at all.

Lets build on them. Who needs open spaces. How dare anyone in London carry out such a pastime. I am also against the use of football pitches (vast areas of open space) running tracks and any other amenities that make people happy. Allotments should also be added as a target, they take up masses of room, people can buy their veg from a supermarket.

We need open spaces, but open spaces that are accessible to everyone. There are 95 golf courses in London, and a further 75 within 5km of the boundary. There’s plenty of space for everyone…it’s just at the moment it’s not evenly distributed.

Many of the golf courses existed a long time before the urban sprawl enveloped them. They have their own history which you are not aware of.

What a brilliant and detailed look at the potential! I had made a mock Government Department website many moons ago (https://abolishgolf.org.uk/) and I’ve taken the liberty to add a link to your great site.

Can we abolish anything / something you like? Football? Tennis?

I don’t want to abolish anything, Bob – just asking why it needs to take up so much space in a congested city like London. No other leisure activity requires the same area as golf – in fact, in London golf courses take up nearly as much area as EVERY OTHER SPORT PUT TOGETHER. Furthermore, each golfer requires something like 1.6ha of land to play – that’s one hundred times more than the area needed for a single football player. That doesn’t seem fair to me.

What about allotments? Why are they fair? Massive use of space for only a few people…

Added together London’s 36,000 allotments take up less than a quarter of the area that golf courses do. So they don’t really compare.

Some interesting thoughts and ideas in there Russell…

Excellent way to start the discussion.. Good luck with it all, although I have a feeling the local NIMBY contingents will cause you grief along the way… J

My thought is ‘who paid?’ and ‘how much?’ for this so-called ‘study’. Either an organisation with a development axe to grind or the tax payer most likely. This is clearly constructed to support a pre-determined viewpoint regarding land use and the assumptions behind it are either highly partisan or deeply flawed. If it turns out that the tax payer paid for this then elected representatives and civil servants have a case to answer. The words of the song come to mind:

“Don’t it always seem to go

That you don’t know what you got ’til it’s gone

They paved paradise and put up a parking lot”

Just because you can research data and perform simple calculations from these, does not mean that the calculations are valid or relevant. Like so much in the public domain these days it is ill-conceived and shoddy.

Nobody was paid for this work, it was carried out entirely in my own time at my own expense. There is no hidden agenda here, other than the fact that I believe golf courses represent a disproportionate and inequitable use of land.

What about allotments? The work of the devil. Only one per person. Surely a target??

Allotments take up less than a quarter of the area that golf courses in London do.

Excellent piece. I have been saying this for years but really good to have some evidence to back this up. They certainly do t meet the tests for green belt and MOL and claims that they help manage the landscape are baloney. We have to be far more creative about land use if we are to help solve the housing affordability crisis but this also provides an opportunity to invest in green and open spaces to make them more attractive and biodiversity. We can also ensure we can improve and broaden accessibility to our green and open spaces so they can be enjoyed by more than a privileged few.

What about royal palace gardens as well?

The Crown owns a few of the courses I’ve marked as privately-owned in the reaserch. Buckingham Palace takes up around 21 hectares – about the same as a 9 hole course in London.

A really thought-provoking study Russell – well done! With the desperate need to find other opportunities to deliver more homes across London where people can also enjoy close contact with biodiverse green spaces surely now’s the time for a fair way to reinvent the fairway.

Thank you for your article. The number of people on a hole depends on the length of the hole. The shortest holes will accommodate up to 8 people at one time, 4 on the tee and 4 on the green. There are very few such holes on a typical course, most are longer and some much longer, accommodating many more people. Slow play is discouraged at every course and I would say the average length of a round is closer to three hours. I suggest you contact some clubs and find out how many people they expect to use the courses in a day. The clubs are of course much busier at the weekends, and tee times are usually spaced very close together. I am an occasional player myself and would very much regret the loss if this amenity, which provides exercise and a close tie to our natural environment – both things which are much needed for the mental health of the capital. I was very dismayed when some years ago, the Golf Centre on the Lee Bridge Road in Hackney was closed.

Tony, thanks for your comment – this is useful to know. The theoretical maximum density of London’s courses together is based on a number of variables, but you’re right that I need to account for more than 4 players per hole at a time. See my later comment to Ernest…I will look at this again.

Excellence piece. I guess it may be time to start a petition.

It is also worth mentioning that golf courses are environmentally unfriendly and have adverse impact on biodiversity. They are essentially huge areas of grass requiring extensive management with herbicides and pesticides, watering, constant use of lawn mowers. They do not support pollinator species and do not pull their weight in carbon sequestration. They are technically green spaces but they are the least beneficial kind.

Hi Kaisa, yes, you’re right that I am not convinced about the biodiversity of golf courses, although I’ve struggled to find much useful writing about this either way. There’s an anecdotal argument that whilst the fairways and greens provide limited biodiversity, the edges are havens for wildlife. This seems sensible, but the same argument could be made about, say, motorways. If you have any references on this subject I’d be delighted to see them.

Great piece, I have also been saying this for a while, there is also a great podcast by Malcolm Gladwell on the subject:

A Good Walk Spoiled – Revisionist History

Listen on Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/revisionist-history/id1119389968?i=1000386572090

I was loosely involved with trying to rewild a golf course in Enfield a few years ago (it didn’t happen – long story) and as part of this spent quite a bit of time talking to people about these sites and visiting them.

What stood out was that some courses in Enfield are important local open space and are used by residents for walking, running, cycling etc. They weren’t just golf courses. I remember one had publicly accessible amenities (cafes, toilets etc.) which were shared with local community groups (running clubs, yoga etc.). It would be good if more were used in this way.

Some sites we looked at flooded regularly, which was interesting from a rewilding point of view, but probably not so good for housing. Two sites we looked at were important sites for flood management and used to help protect housing in other parts of the borough from flooding by keeping water upstream. Large parts of the courses turned into lakes when it rains (which looks quite nice and should probably be considered as a more permanent blue/green infrastructure).

In terms of wildlife and nature; I wouldn’t say golf courses are good in this respect, but the ones we looked at did seem to act okay (in that it could be much worse) as buffers to protect surrounding areas of Metropolitan Importance for Nature Conservation and ancient woodland that surrounds them.

There is a problem with some of them. Public access could definitely be improved across quite a few of the courses, especially those closest to town centres (e.g. the one bordering Town Park) and urban areas like the Lee Valley, and it would be good if they found ways to improve biodiversity across the playing areas.

Housing? Possibly, but personally I have doubts that the housing built on golf courses (in Enfield at least), especially those in green belt areas will reflect local housing need. We need 7,500 social rent homes and around half of these need to have 3+ bedrooms. I wonder how many of these would be delivered by building on Crews Hill golf course?

This is an important conversation to have in London, so well done on getting it going.

Hi Matt, thanks for the comment. I agree with you, and my argument (despite how it’s being perceived in some quarters) isn’t just about housing – although I do think that’s part of the solution. The main issue is the inaccessibility, which clearly affects some courses more than others. But the piece has certainly stimulated a debate, which was the objective.

Great article. Detailed, thorough, convincing. Many thanks.

Great work!

There’s one in Southwark you missed: https://www.aquariusgolfclub.co.uk/

What Lewisham did to Beckenham Place park should really set a precedent. It’s now such an amazing space, one of my favourite parks in London. Crazy to think this would not have been accessible to most people several years ago.

Thanks, Leon, someone else has pointed out Aquarius Golf to me too – not sure why it was missed, but I suspect it’s not listed as a golf course on the OS Greenspace dataset, which is what I used for the research. I’ll have another look at add it in.

Seconded – I’ve seen Beckenham Place park. More’s the pity Southwark isn’t extending the same care to its council-estate residents’ green/environmental assets, instead intent on building its across-borough ‘infill housing’ on many of those estates. The most egregious example of this environmental destruction is the imminent loss of Peckham Green (on Twitter @peckham_green), Infill is a London-wide programme set up by the present mayor in 2018 during Sadiq Khan’s first term – https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/housing-and-land/increasing-housing-supply/building-council-homes-londoners. Islington’s Dixon Clark Court scheme, alongside Southwark’s Peckham Green are examples of bad infill. Some background info via Islington Tribune: ‘We have been warned on the loss of green spaces’ http://islingtontribune.com/article/we-have-been-warned-on-the-loss-of-green-spaces; and ‘Densifying our borough is not very “people-friendly””: http://islingtontribune.com/article/densifying-our-borough-is-not-very-people-friendly. Depriving some of the city’s poorest and most vulnerable residents of their environmental amenities is no way to solve London’s affordable housing crisis, particularly in these pandemic times. The mid-pandemic, August 2020, introduction to City Hall’s London’s Green Spaces Commission Report makes for particularly interesting reading: ‘public realm includes…green areas in housing estates…essential for [the city’s] biodiversity and in boosting resilience to climate change’ (https://www.london.gov.uk/WHAT-WE-DO/environment/environment-publications/london-green-spaces-commission-report). FYI: one of the commissioner’s of this report is the boss aka director of Islington’s Environment and Regeneration department (ref Dixon Clark Court above).

This is why Russell’s piece is timely: it can only help focus minds on long-term solutions to our capital’s housing crisis, in part the result of London’s obscene property prices.

You wouldn’t believe it, but just a few days ago I was walking alongside a golf course (I’m Italian and I was in Switzerland, so it’s not a common sight in this part of Europe) and I was wondering exactly how many golfers at a time could occupy a golf course.

Thanks for the article, very insightful – I’m not a golfer nor an architect but I live in a densely populated city (Milan) and use of land and spaces is something that I care about.

Very interesting, Russell. I carried out a project whilst at the RCA in 2013 looking at the sheer quantity of golf courses in the metropolitan green belt and how a relationship with future housing could be developed. It was great fun exploring the potential scenarios between golfers and tenants, so it was very refreshing to see another take on this 8 years on.

In 1992 George Carlin proposed housing for the homeless built on the substantial wasted space of golf courses.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GchEbLSY9FY (bad language)

I enjoyed this and agree there should be more discussion and scrutiny of golf course land use in London. However, from my knowledge of Richmond and SW London, the courses on publicly owned land may well be in places you wouldn’t want to develop because they’re inside/next to parks (Old Deer Park, Richmond; Wimbledon Common, Home Park). Its the courses that are 100% private and fenced off from public access that would make excellent development zones IMO (Strawberry Hill, Fulwell)

I agree with a lot of this. We live in Redbridge where they are considering felling several old trees near our estate to build more houses, but no mention of the golf courses! Also, I think Fairlop Waters Golf Course might be Council owned -https://www.golfshake.com/course/view/14701/Fairlop_Waters_Golf_Club.html

Hi Heather, thanks for the comments – I’m not sure about Fairlop Waters…the Land Registry seems to suggest that the freehold is owned by private individuals rather than the local authority. Have you found any information which suggests otherwise?

https://visionrcl.org.uk/sport-health-physical-fitness/sports/golf/

https://visionrcl.org.uk/about/

It’s run by ‘Vision’ which is a charity that receives the funding from the council. They provide all leisure facilities in the borough, including parks and sports. Not sure where it sits on your scale then, but I would still have said LBR.

AAh, interesting. I’m not sure that fulfils my definition of publicly-owned (I’ve applied this to the ownership of the freehold rather than leasehold), but interesting to know. I’ll add a note to the specific course information.

You might be right. Many thanks for putting all this together, very interesting!

It’s an interesting study if rather weakened by a lack of understanding of golf, the game, the capacity constraints and opportunities, the social benefit, and to my mind a key point the environmental benefits (less green lungs and wildlife space) which surely has a very large benefit and thus worth. But if space was at a premium I could support the premise, but there is an absolute surplus of brownfield land and empty developments, not to mention empty overseas owned big houses. Wouldn’t you prioritise sorting these areas before paving over grass and trees and streams and ponds?

Hi Nick, thanks for the comment. Others have responded with further detail on the technicalities of the game which has informed some of the figures. I’m not convinced that golf courses actually provide as much in the way of biodiversity as one might imagine, given their water use, monoculture and heavy mowing. The social infrastructure they provide is not in question, but my point is that this is limited to a very small proportion of Londoners, and alternative uses might provide better social value, benefitting many more. The binary choice between “green fields” and “concrete” is also a fallacy: we can choose to develop new homes in a sustainable, biodiverse manner; whether we choose to is a different matter. You’re absolutely right about brownfield land too, but to meet the housing demands of London we need to examine all options available to us. It’s not a matter of either/or.

Now may be the time for a ‘rational discussion about whether golf courses still represent an optimal use of land’ but this isn’t it. Your bias and ignorance are sadly showing. You could at least have done a bit of user research and talked to some golfers.

Firstly you don’t demonstrate that lack of developable land is a major cause of the shortage of affordable housing in London. You’ve jumped to a ‘solution’ without analysing the problem.

As others have pointed out you underestimate the use of golf courses Tee slots are typically every 10 minutes, so on an 8am to 6pm day that’s potentially 240 golfers teeing off for a round of 18 in a day. At peak occupancy: 4 golfers teeing off every 10 minutes for 4 hours that’s potentially 160 golfers on an 18-hole course at one time. Of course, in practice, that level of usage will only be achieved occasionally, But there will be other uses of the space in practice areas, etc and of course the 19th hole!.

Your claim that “the same area occupied by a single golfer could provide a home for around 380 people.” is entirely spurious- the golfer is just passing through a shared space not occupying it permanently. Your not comparing like with like.

You claim that golf is “only enjoyed by around 1% of the national population” but according to this there are over 1 million active golfers in the UK https://www.statista.com/statistics/899231/golf-participation-uk/

Golf is not as elitist or inaccessible as it’s perceived. The main barrier is probably time which is why it’s popular with retired folks. For whom it’s also good exercise. You mention the Perivale Course, which is currently under threat of closure. A round there during the week is less than £10, and 2nd hand clubs can be bought pretty cheaply. Closing courses like this will actually make golf less accessible.

Perivale, like other municipal courses, is open to the public for other purposes and it’s common to encounter dog walkers there. Though there are obvious risks to being in an area where small hard objects are flying at speed!.

Yes, I’m a golfer and a member of a golf club. I only took up the sport recently and I’m well aware of the privilege of having access to so much green space. Golf does need lots of space. But I’ve also been pleasantly surprised about how little golfers fit the stereotype (though as I’m from Scotland not that surprised.)

Yes, let’s have a rational debate about the scale of provision, it would be helpful for you to produce an improved version of this. But also let’s be careful and explicit about what’s meant by ‘optimal’,